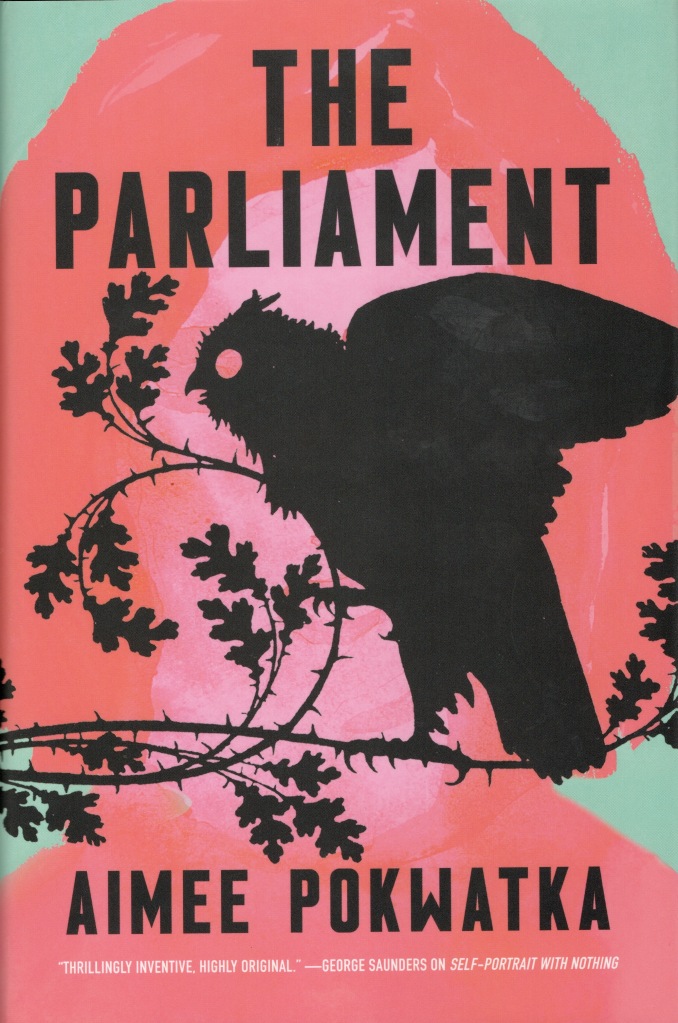

A parliament of murderous owls traps a disparate collection of people inside a small town’s public library. To try and keep the children calm and distracted, as well as pass the time, a fantasy story is read aloud to them…

“Its The Birds meets The Princess Bride” might be a terrific elevator pitch for The Parliament, but it also creates an anticipation, or hope, for a very different kind of reading experience than what the book actually delivers.

Then again, maybe my own disappointed expectations are to blame here. Because both The Birds (film) and The Princess Bride (source novel and film adaptation) were seminal influences on me, I think my own idiosyncratic experiences with them colored my expectations of what The Parliament was going to deliver.

The first third did have the kind of apocalyptic dread that saturates the latter half of The Birds, but the mood is fractured and diluted whenever the book within the book, a fantasy novel titled The Silent Queen, interrupts and takes the narrative stage.

For the first half of the book I was zipping through chapter after chapter, eager to find out where each story was heading and how they would play off of each other. But as the siege dragged on, and the fantasy trek went through the standard “Hero’s Journey” tropes, I yearned for some of the darker, more biting commentary that made William Goldman’s novel so memorable.

But Aime Pokwatka is not William Goldman and The Parliament is not The Princess Bride (novel, not film). Which is a good thing.

While I do appreciate the thoughtful examination on how trauma, loss, grief, and healing impact different people in different ways, I also must admit that The Parliament was a chore to finish. Not because it was bad or boring, it just did not meet my own weird expectations of what The Birds meets The Princess Bride should feel like. So it goes.